Somewhere, stashed away in a cardboard box stored in my basement, is my old catcher’s mitt. I used it when I played Little League in elementary school. It fit my hand then. Now my hand is almost the size of the mitt itself.

I have kept the mitt because it reminds me of those early years when I was first learning the game of baseball. Originally, I had simply played catch with friends. It was our everyday routine after school in one another’s backyards. And all of us imagined ourselves as major league pitchers. We had pitch backs set up as soon as there was more mud on the ground than snow. I acquired the catcher’s mitt so that we could all be a bit more daring and adventurous in flinging baseballs to and fro. But soon the mitt became useful in positioning me on the field, as the casual exercise of playing catch progressed into more formal attempts at succeeding in actual games. We graduated up into uniforms and fields with dugouts and fences. There were rules and strategies to apply. Coaches instructed us from the sidelines and umpires gave their assessments. Some teams were dominant and daunting. Others seemed unusually inept. We graded our play by our record of wins and losses.

The more I played, the more I loved the game. I still do, though I’ve regressed back to merely tossing baseballs with aspiring grandsons. I consider myself a traditional fan and someone who is relatively well informed about what makes baseball the best of professional sports. And I never took a class on it. I’ll admit that I’ve got a good number of books on the subject, but they’re largely memoirs or histories or nerdy investigations on how the science of physics determines the limits of play. I learned how to gauge fly balls by running them down. I figured out how to throw a passable knuckleball by hours spent practicing it. My respect for curveballs comes from trying to hit them — and mostly failing. And I know viscerally, from experience, that there are few things in normal life as frightening as the crack of the bat and that split second moment of realization that the only thing that will prevent the serious injury of being hit by a screaming line drive is the speed of one’s reflexes. More than all else, the play’s the thing. Nearly sixty years on, I’m still eager to slip a mitt onto my hand. And when my grandsons imagine being big league infielders, mimicking the style of favorite players, spinning as they flip the ball my way, I recall the dreams I once had. They’re still in my head.

I learned faith in much the same way. I went to church — which is a shorthand way of saying that I was regularly given the experience of worship. I wasn’t first taught about it. I was immersed in it. Before I was old enough to have a catcher’s mitt I had to endure sitting quietly through long prayers and interminable sermons (forty minutes). I had no idea what was being said. That didn’t really matter. What I intuitively knew was that all the talk was important to my mother, as it was to the adults who were sitting all around me. They maintained a remarkable patience and respect. Church was where I experienced reverence. It was evident in how people sat and how they interacted. It was visible in the appointments of the church, in robes and carved wood and stacks of silver trays for the distribution of communion. I was expected to show discipline, paying attention to things I had no way of understanding. It was my initial introduction to the idea that there was something more important than me.

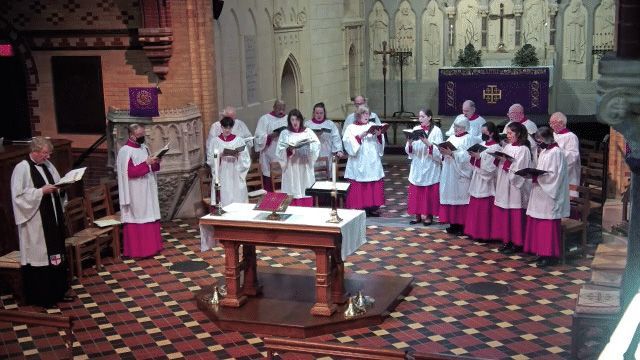

I did enjoy the hymns. They offered an opportunity to stand and make some sound. And as I heard the voices around me, this could be amazing or appalling. I learned the word “shrill” by listening to others sing. I also remember the first time I heard someone shift to a bass line, singing harmony. I was enthralled. I was too young to sing in that register, but I decided then that I would do the same, hopefully as beautifully, when the future opened this for me. By the time I was running base paths, I was singing in a church choir. I didn’t know how to read music; that didn’t really matter. I picked this up through listening, joining my voice with others.

I became an acolyte when I was in middle school. It was a noticeable step up: different robes, white gloves, processing with flags and crosses, leading people in and out. Discipline in worship moved from obligation to responsibility. At crucial points in every service, I was in charge. People looked to me. I had standing. And I wanted to be well-regarded by those who, spanning many years, afforded me this charge. Those in the pews let me know with their eyes and smiles that they had expectations of me; I did not want to disappoint them. And it was then that I started to realize that the readings and the prayers and the responses and the sermon that comprised worship meant something. People waited upon these, so I decided to do the same. Many Sundays I sat in an appointed seat just behind the pulpit, in clear view of everyone. In order not to be distracting, I trained myself in listening. I learned the cadences of Scripture and the rhythms of preaching. I discovered the poetics of both. And the words that were spoken were meant to address the deeper yearnings of life, in ways that a conversation or discussion couldn’t.

I knew a lot about the Bible, more than most around me. I attended a private, Christian school. Daily religious instruction was a requirement. And I participated in Church School, which was little more for me than a watered-down reiteration of what I had already been taught. I appreciate this now more than I did then. I wish I had paid more attention in all these classes. But something about all of this felt like language out of context. God isn’t merely a topic to be covered or an object to be dissected or an idea to be argued about. One can’t learn one’s way to worship or graduate from Church School with a command of the subject. Above all, faith is a practice, nurtured in the experience of communities: the community of the parish that gathers, the community of voices of Scripture, the community of the saints before us, just to name a few. Faith is an engagement of word and song and gestures. It is our placement of ourselves before God with the same kind of anticipation and eagerness that one might feel when crouching behind home plate and waiting for a pitch. It has that freshness, no matter how many times one has played catch. Faith can only be learned by exercising it.

Part of the malaise of religion in our time stems from the loss of the primacy of worship. Instead of experiencing it as faith in action — and at the highest levels — we treat it as a clumsy means to other ends, as if we’re contemplating the possibility of God rather than encountering him, as if the real work of community happens outside the church walls. The great blessing of the worship at The Redeemer, however, is how, on so many levels and inclusive of all ages, it invites participation and interaction. It’s easy to take this for granted and not see just how much is happening and what it means. But once it’s noticed, then the many components of worship reveal the heart of worship. And the heart of worship makes God’s presence palpable and true, for us and between us. And it never grows old or becomes outmoded. And it’s this that makes the Christian life possible.

In an early journal entry, the noted monk Thomas Merton recalled an experience he had one morning after he had traveled down from the monastery into town to see a printer about some pamphlets that were being prepared for persons who might be interested in pursuing monastic orders. His comments are worth quoting. He wrote: “In Louisville, at the corner of Fourth and Walnut, in the center of the shopping district, I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realization that I loved all these people [who were wandering about], that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers. It was,” he said, “like waking from a dream of separateness [and] of spurious self-isolation.” This is the realization that worship makes uniquely possible. More than all else, the play’s the thing.